When people ask what will happen to the decades of yearbooks, trophies and other memorabilia inside Henry Elementary School when it closes this summer, Tiffany Herman doesn’t have answers.

The PTO secretary and her fellow board members are first working on allocating the remaining money the organization raised for the school before it has to dissolve its nonprofit status.

But her biggest concern right now is trying to get her younger daughter excited about going to fourth grade at a new school.

Herman took her two daughters, who will be entering fourth and fifth grade in the fall, to an open house at Ferrum Elementary last month.

“I don’t want to be here,” the younger one said, reluctant to participate in a scavenger hunt for new students to learn about the school.

“I understand, sweetheart,” Herman said she told her. “But nobody here at this school had anything to do with your school closing.”

They’re trying to make everyone feel comfortable and make the best out of a difficult situation, Herman told her.

“So let’s give them a try.”

* * *

Henry Elementary is one of two schools completing their final academic years on Wednesday in Franklin County, one of several school divisions in Southwest and Central Virginia facing ongoing declining enrollment and the funding challenges that often accompany it.

In some places, the closures have come on slowly, the result of years of discussion and weighing options that can soften the blow when it’s finally time to shut a school’s doors. In others, like in Franklin County, the decision to close Henry and Burnt Chimney elementary schools happened fast.

“I didn’t expect it would happen this quick,” said Superintendent Kevin Siers, who is wrapping up his first year in the role in Franklin County. “I thought we would have a couple of years to work through the process.”

Declining enrollment over the past two decades has left the division with less per-student state funding than it used to get. Since the 2006-2007 school year, the number of students attending public schools in Franklin County has dropped by 20%. Henry Elementary, where Herman’s girls attended, has space for 244 students. This year, it served just 165 pupils across seven grade levels.

The division commissioned an efficiency study in fall 2022 to look at options for consolidating some of its 12 elementary schools, all of which were operating below capacity. Burnt Chimney, which was at about 70% capacity, made the list for its proximity to two other schools, along with the fact that it was due for costly building maintenance, Siers said in an interview.

The report was delivered in summer 2023; it recommended that the division consider closing up to three elementary schools. But just a few months later, division leaders got bad news: A change was coming to the local composite index, the calculation of how much a local government must pay toward its schools after state funding is allocated. Franklin County was getting ready to lose $3.7 million in state money that it had been counting on to balance its budget.

By the end of February, the school board had decided to close two of the county’s 12 elementary schools. That, plus reducing some secondary school teaching positions via retirements and voluntary departures, would free up just enough money to cover the budget deficit.

The board vote came amid outcry from residents, including some whose families had attended these small elementary schools for generations.

“Not acceptable. Not on my watch,” wrote Sen. Bill Stanley, R-Franklin County, on Facebook after the vote to close the two schools. He had spoken at length during the board’s public hearing a few days earlier, pleading with the school board to hold out to see what funding would look like once the state budget was finalized.

But board members said they couldn’t afford to wait.

Closures were decided with similar alacrity in Russell County, where the school board voted a few weeks ago to close two small elementary schools at the end of this academic year. Division leaders cited declining enrollment and budget concerns, acknowledging that it could either keep all the schools open or give teachers raises in a county where starting pay is $36,000 a year; but it couldn’t do both.

Lynchburg plans to close or repurpose two elementary schools at the end of next year after years of community debate over how to manage declining enrollment and aging school infrastructure.

In March, Bedford County rejected a proposal to close a 112-year-old elementary school. But school board members acknowledged they will need to continue conversations about closing schools as the division prepares for a state funding cliff in 2028.

Enrollment in Virginia public schools started slowing down in the early 2010s, spurred by a combination of people leaving the state, newcomers without children moving in, and a Great Recession baby bust.

Ten years after that decline became obvious, the pandemic exacerbated the situation. Some families decided to stick to the online learning or homeschooling that they had grown accustomed to during the pandemic, while others switched to private schools.

Projections from the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia expect three in four school divisions in the commonwealth will see enrollment continue to decline between now and fall 2028.

Across most of Southwest Virginia, student enrollment is projected to drop at least 3% over the next four years. In counties including Patrick, Carroll, Tazewell and Buchanan, the decline is expected to top 6%.

Lower enrollment means a school gets less per-pupil funding from the state.

But many of the school’s expenses stay the same. A classroom still needs a teacher, supplies and heat in the winter, regardless of whether it has 20 students or 12. If division administrators see kindergarten classes getting smaller year after year, it can send off alarm bells that balancing the budget is going to be even harder for a span that could last a decade or more.

But deciding to close a school is harder than looking at a spreadsheet and deciding where to cut, where to shuffle kids around to fill seats in classrooms elsewhere in the county that have space.

“For some school communities, the school is central to its identity and reflects its values and beliefs,” said Margaret Constantino, executive associate professor at the William & Mary School of Education. A school division has to strike a balance, she said, to be fiscally responsible while also being sensitive to the needs of the community.

But, she said, sometimes the tough choice just has to be made for the long-term benefit of the school division.

“Sometimes there are no options.”

* * *

Jacob Wright and Jonathan Arritt have been through this before.

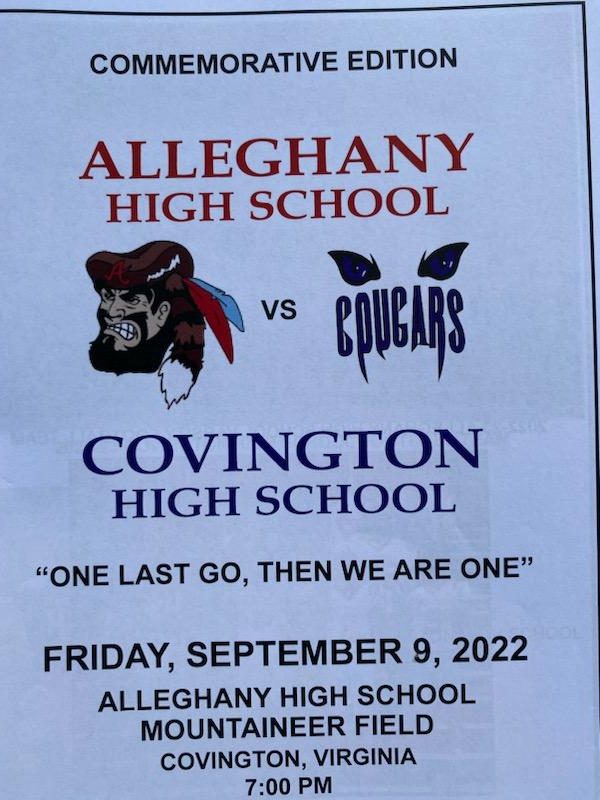

They used to be school board members for adjacent school divisions, with Wright on Alleghany County’s board and Arritt on the board in Covington, the independent city right in the middle of the county.

Now they’re on the same school board. The two divisions merged in 2022, after more than a decade of debate, to become Alleghany Highlands Public Schools.

Population decline was the primary factor, especially after the Lear Corporation, which made automotive door panels, closed its Covington plant in 2005. Over a 15-year period, the two school divisions combined saw enrollment drop by 22%.

Alleghany County considered closing three of its five elementary schools. It ended up closing two of them in 2013, requiring about 250 students to change schools.

Wright thought the process was too political and didn’t like the new bus routes that put some students on the bus for nearly two hours. It motivated him to apply for a seat on the school board, which was at that point selected by board of supervisors’ appointment, not election. He’s now the chair of the consolidated board, which has switched over to an elected model.

“It was definitely a turning point,” Wright said of the contentious 2013 closures, as many who watched the process of deciding which schools would close didn’t want to go through it again. He said a lot of people “had been comfortable with these little elementary schools. Everybody had a little neighborhood elementary school, which is what we do really well here.”

“I think maybe it did turn some people to say, ‘We’ve been separate for a long time, and separate is just getting us closed elementary schools,’” recalled Arritt. He’s the vice chair of the consolidated board.

The school boards voted to merge in 2020. The first step of the consolidation took place in July 2022, with the merger of the two central offices and school boards. Students didn’t change schools until the start of the 2023 school year. Older students experienced the greatest change, as Covington High School converted to the division’s sole middle school and Alleghany High School became the new division’s single high school.

The consolidation had its opponents. “The number of extremely negative comments on Facebook was substantial,” Arritt said. But more often, when he’d talk to someone one on one, they’d tell them that even though they didn’t want the schools to consolidate, they understood the reasons why it was being considered, he said. “They also understood the connection between the economic health of your area and the opportunities you’re able to give your students.”

Ultimately, the consolidation smoothed out disparities in the student experience at the career and technical education center that the divisions had run together prior to the merger. Across the new division, Alleghany Highlands has been able to add electives and extracurricular activities that neither of the two divisions could offer on its own in recent years.

Those opportunities have been added at the same time the consolidation saved $450,000 in personnel costs in its first year alone.

A promise to merge without layoffs made the consolidation a little easier to embrace. Keeping all the elementary schools open helped, too.

“People get a lot more emotionally charged when you’re closing elementary schools,” Wright said, because parents are so protective of their small children.

“These divisions around the state that are having to choose [whether to] close elementary schools, they’re going to have a fight on their hands for sure.”

Elementary schools tend to be smaller than their secondary-level counterparts, in part to ensure smaller class size and personal attention. Small schools are also known to foster community involvement.

A dozen elementary schools might seem like a lot for a single county. Nearby Montgomery County has eight elementary schools for a county population that’s about double of Franklin County’s. But Montgomery County spans about 400 square miles, while Franklin County schools cover an area of more than 700 square miles.

Small schools keep kids close to home. And as schools close, transportation times lengthen. New consolidated bus routes mean elementary students in Franklin County could ride the bus as long as 55 minutes to get to school.

Siers recalled speaking with Kimberly Hooker, superintendent of Russell County, as her division’s board discussed school closure options that mirrored Franklin County’s. He said the anxiety around the decision was familiar. “It’s a really tough call to make. Small elementary schools love our kids, take care of our kids, and have been a part of our communities for decades.”

He said that Franklin County was fortunate that despite closing two buildings, “Students are still going to small, very community-oriented elementary schools.”

The remaining elementary schools were all designed for up to 350 students, Siers said. None of them will be at capacity after the consolidation.

* * *

The long run-up to the merger and the close proximity of Covington within Alleghany County made some adjustments easier during the merger.

“Our kids are already in sports, dance, church together,” said Rachael Thompson, a parent of three who lives in Covington. “Families are already combined.” She even joked that she was already in a consolidated household, because she and her parents went to Covington High while her husband attended Alleghany High School. “Everyone likes to accentuate the divide, but this area is close knit.”

But that’s been different from the experiences of families living in Franklin County or Russell County, where the idea of closing schools went from option to certainty in a matter of weeks.

That turnaround shock can mask some of the positives of consolidating schools. In Franklin County, for example, the division will now be able to afford full-time teachers for gym, art and music, along with a guidance counselor, in each elementary school, instead of sharing those staffers among several locations.

“We tried to show how we could become more efficient and improve services to students, even though we’d have to take some undesirable steps to get there,” Siers said. He said feedback from families has been “increasing in positivity” as it gets closer to the start of the 2024-2025 school year. Open houses for students and families along with field trips to students’ new schools for activities have helped. “It’s been a tough situation for a lot of our families, but there’s a pretty high degree of acceptance,” Siers said.

Much of the success — or the perceived success — of consolidating schools comes down to communication, said Constantino, the professor at William & Mary.

“If the level of engagement and communication has been high, then there will be trust within the school community. In this case, the community may not like the decision, but they may better understand it and their voices will have been heard.”

But that communication should start before reaching the critical point of deciding to close a school. “These problems do not occur overnight,” she said, adding, “School and community leaders must keep an eye on the horizon to best prepare the school community for what is ahead.”

In Bedford County this spring, the debate over whether to close Stewartsville Elementary School stemmed not just from declining enrollment, but also from the condition of the building. Stewartsville is next on the division’s list for major repairs including a new roof and HVAC system that it expects to cost somewhere in the realm of $20 million. Close the school soon could avoid those major expenditures, allowing for investment elsewhere in the division.

“We have more discussion to do,” board chair Marcus Hill said after the board voted against closing the school right away. “Because at the end of the day we don’t have the funds to maintain our facilities. We don’t have the funds to add additional programs. We don’t have it.”

He said efficiency discussions need to be a priority once the board selects a new superintendent. “We’ve got to have not just a one-year plan. To benefit those who will be in our seats in 10 years, we owe it to them and to our community to be prepared of what’s next.”

In Lynchburg, the approach has differed. The communities of T.C. Miller and Sandusky elementary schools have known since September 2023 that their schools would be closing in summer 2025. But as the board reviewed budget options for the upcoming school year, members of a group called Save Our Schools that has advocated for keeping the two schools found a line added into one of the budget scenarios that listed Miller and Sandusky closing at the end of this school year.

When the parents raised the issue at the next school board meeting, vice-chair Martin Day responded by saying that the line item to close the schools early was added to make a point.

“All this is saying is, ‘What if the city says no?’” The board had expressed concerns that the city council wouldn’t be willing to give it more funding to fill a budget deficit for the coming year. “It’s just making the point that we may be faced with that level of a decision.”

If it was a scare tactic to spur action from city council, it worked: the council voted in May to pitch in $1.6 million if necessary to keep the two schools open for the next school year as originally planned.

But the move may have further eroded trust with T.C. Miller and Sandusky parents, who have been on high alert since they found out last September their schools would close. Even though T.C. Miller and Sandusky were both on the list of options shown to community members for feedback, Sandusky wasn’t included in the recommendation made by both an outside consultant and the board’s finance committee; it was a surprise addition the night of the full board’s vote.

* * *

In Alleghany Highlands, Thompson acknowledged that her kids all stayed at the same elementary school, and won’t see the major effects of consolidation until her oldest goes to middle school next year. But she said despite some trepidation from the community, the consolidation seems to be viewed positively for the most part.

“People get lost in the details, and parents get lost in being concerned with their children,” Thompson said. “But think of it from the children’s perspective.” If parents can focus on the positive aspects of moving to a new school, she said, it may ease the transition for the young people affected most.

That’s the mindset Herman is trying to keep as she prepares her girls for their new school.

She’s not thrilled about a long and winding drive to take them to Ferrum Elementary each day, for which she says, “There are no sneaky shortcuts.” She wishes the process of deciding to close the two schools in Franklin County had been more transparent. She’s felt defeated. She’s felt frustrated.

“But it doesn’t do our kids any good to have that negative atmosphere,” she said. “It just sets the wrong tone.”

So she and the other parents at Henry Elementary are putting on brave faces, she said. The PTO has been focusing on marking the end of the school year. “Let’s just make the best end of the year we can,” she said. “Kind of go big with everything.”

Henry Elementary and Burnt Chimney each hosted an open house in early May so community members and graduates could walk through the halls one last time. Herman talked about keepsakes the PTO might order for the last group of students to walk out of Henry in May.

And at field day?

It’s obvious she’s smiling as Herman walks into another room of her house, so her older daughter won’t hear her whispering into the phone.

“There’s going to be ice cream.”