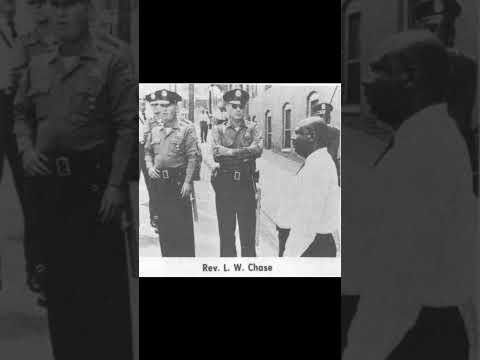

Through the scratches and blips of the 57-year-old audio comes the strong, even voice of the Rev. L.W. Chase, explaining to the judge and jury why protests for equal rights have been so important in Danville.

“The proposal of going around the conference table and sitting down and adjusting legitimate grievances doesn’t seem to work,” says Chase, standing trial in 1966 on charges that he violated an injunction prohibiting civil rights demonstrations. “The struggle will not cease until we attain our full citizenship, and so that’s why we are in this court today.”

Another audio file preserves the voice of Eugene McCain, Danville’s police chief at the time, testifying about law enforcement’s response to the demonstrations on June 10, 1963, which became known as Bloody Monday.

“We turned the fire hose on them [the protesters], and they ran down the alley,” McCain says during another 1966 trial. “I told the police officers to arrest more of them, and they went out and got a group of them out of that bunch and put them in jail. And then another fire truck hooked up a hose on the Patton Street side … and turned the hose on them at that time from that direction.”

These recordings are part of a collection of records from Danville’s civil rights movement, which resulted in hundreds of trials that lasted about a decade.

The judge, a staunch segregationist, excluded almost the entire public from the court proceedings.

But today, anyone can visit the Danville courthouse or the Library of Virginia in Richmond and read court documents or listen to audio of these proceedings.

Hearing the voices of the protesters and the lawyers “makes you feel like you’re there,” said Gerald Gibson, the clerk of circuit court in Danville. “It’s as if you’re sitting in the courtroom at that time.”

Gibson, who has listened to all 85 hours of trial audio, said the collection was discovered in a storage area in the 1990s. He believed that the material should be better organized and accessible to the public, he said, so he contacted the Library of Virginia to help preserve the collection.

“One of the reasons for doing this was so that anybody interested could come in and actually see and listen,” Gibson said.

Civil rights protesters themselves say they don’t remember all the details from these trials — partly because they happened many decades ago, and partly because the court proceedings don’t stand out as vividly in their memories as the actual protests.

Carolyn Wilson, who still lives in Danville, called the trials “anticlimactic” compared to the excitement of the demonstrations.

Dorothy Moore-Batson, who went to court twice for her involvement in the movement, agreed. But she does have memories of Judge Archibald Aiken and the Black attorneys who represented her.

Some protesters, and some of their children, have visited the courthouse to listen to the trial audio, said Gibson.

Here’s the story of the trials that followed Danville’s civil rights movements and the effort to preserve the court records.

* * *

“Ain’t nobody told me nothing about an injunction at all. … I didn’t learn about the injunction until I was in jail.”

— Demonstrator Stuart Walter Mayo’s 1966 testimony about his 1963 arrest

The Danville civil rights protests began on May 31, 1963. By mid-July, more than 250 people — almost all of them Black — had been arrested on charges including contempt, trespassing, disorderly conduct, assault, parading without a permit and resisting arrest.

Most of these charges came under the umbrella of violating a city injunction that limited protests and public assemblies. On June 6, Aiken issued this temporary injunction, which later became permanent.

More from the bloody monday series

The city began to use a Civil War-era statute to charge and arrest protesters.

This 1859 statute had its origins in slavery and made it a felony to conspire or to incite “the colored population of the State to acts of violence and war against the white population,” according to Encyclopedia Virginia.

Many of the demonstrators were teenagers, which meant that parents were sometimes held responsible for their kids’ involvement in the demonstrations.

“Parents were arrested when they went to the jail to post bail for their children for contributing to the delinquency of a minor by not providing adequate supervision,” according to a Library of Virginia guide to the collection, written by former archivist Jay Gaidmore.

The trials began June 17. Almost immediately, the defense teams sought intervention from federal courts, on the grounds that a fair trial could not be had under Aiken in Danville.

“It’s not surprising that the protesters and their lawyers looked to the federal courts to vindicate their rights when the Virginia state courts sort of broke down,” said Thomas Frampton, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law who specializes in the intersections of criminal law and race inequalities.

But the federal courts did not provide any relief. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals declared Aiken’s injunction constitutional and cases were remanded to the local court.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision by a 5-4 margin.

“It’s disheartening to see how the federal courts effectively allowed these reactionary state government figures to get away with really outrageous and blatantly unconstitutional things,” Frampton said.

By August 1963, hundreds of people were awaiting trial and bail bonds totaled an estimated $300,000 — over $3 million in today’s money.

There were so many individual cases to be tried that the courts dockets were “filled to such an extent that cases separate from the demonstrations could not be heard,” Gaidmore wrote.

The team of defense attorneys agreed to consolidate cases, so instead of having a separate trial for each individual, defendants were tried together without a jury.

This expedited the process and also helped avoid venue changes that would have scattered the trials across other Virginia localities to alleviate the volume of cases in Danville.

Aiken was known to hand down harsh sentences, according to Encyclopedia Virginia. But he did not find every defendant guilty, dismissing some cases for inadequate evidence, according to the Library of Virginia.

A typical sentence was eight days in jail and a fine of $20, or around $200 in today’s dollars.

“The demonstration leaders received the stiffest penalties with Rev. Lawrence G. Campbell receiving the worst, being sentenced 250 days in jail and a $2,500 fine,” Gaidmore wrote. This amount would be more than $20,000 today.

By 1967, appeals from these cases had made their way to the Virginia Supreme Court. In 1973, the Virginia Court of Appeals heard the last of the cases from the demonstrations.

“The Court overturned the convictions of almost 270 people,” Gaidmore wrote. However, it “upheld the convictions of those named in the injunction,” who were the leaders of the movement: Campbell, Julius Adams, the Rev. L.W. Chase, the Rev. A.I. Dunlap and Arthur Pinchback.

On Feb. 9, 1973, the court proceedings finally came to an end, almost 10 years after the day of the first demonstration.

Aiken had died in 1971 of a heart attack. Judge Glynn Phillips Jr., who was by now handling the cases, suspended jail sentences for the movement leaders whose convictions had been upheld by the state Supreme Court, on the condition of good behavior for two years. Phillips also ordered fines that totaled more than $5,000, or about $34,000 today.

It’s staggering how long these cases lingered in the courts, especially because the arrests were made over the course of only a few months, Frampton said.

“In some ways, it feels like it just adds insult to injury to have people seeking justice through the courts, when the courts had long ago been effective in dismantling and neutralizing the really exciting organizing that was happening in the streets,” he said.

* * *

“We could not arrest everybody. …We didn’t have sufficient personnel. We tried to arrest those that we thought were leaders and those that were doing most of the noise and encouraging the others.”

— Police Chief Eugene McCain’s 1966 testimony about the 1963 demonstrations

Moore-Batson remembers sitting in a Danville courtroom in July 1963, after being arrested for leading a march. She was surrounded by other demonstrators while Aiken lectured them about violating the injunction.

“It was a full house,” Moore-Batson said. “It was a small courtroom, and there were so many of us. I think some of us were able to have a seat, but I remember many of us standing.”

Aiken’s courtroom procedures drew national criticism from Martin Luther King Jr. and the U.S. Department of Justice, among others.

“He excluded virtually the entire public, kept a large force of armed police present, required all defendants to attend roll calls every day, subjected the defendants and their attorneys to daily searches for weapons, and banned discussion of the constitutionality of the injunction,” according to Encyclopedia Virginia.

If a fair judge is the baseline, and if most judges in the South at the time were off baseline, then Aiken was a complete outlier, said Paul Gentry, a Danville historian who volunteers with the Danville Historical Society.

[Coming Tuesday in Cardinal News: Who was Judge Archibald Aiken?]

“He was really out of line,” said Joe Scott, an archivist with the historical society. “He was known as the ‘pistol-packing judge.’ He really made his own path.”

But Aiken was praised for his courtroom conduct by others, including the all-white Danville Bar Association, which publicly voiced support for him. The historical society has an entire folder of “fan mail” that Aiken received from elected officials, local businesses, politicians and Virginians throughout the state for his handling of the civil rights movement.

Unsurprisingly, Aiken was widely disliked among the protesters, said Moore-Batson.

“He appeared to me to be an angry little man,” she said. “He yelled and screamed and turned red in the face. And I never heard anyone say anything nice about him.”

But the protesters were not afraid of him, Moore-Batson said.

“I think we kind of expected that behavior,” she said. “For most of us, probably for all of us, it was the first time we had gone to a courtroom to appear in front of a judge.”

There was no jury or testimony involved, she said. It was just Aiken speaking to the group.

“It was not a trial, and I don’t know if you can call it a hearing,” Moore-Batson said. “We just had to appear before him and maybe that was the way they did things. You had to appear so he could tell you why you were arrested.”

Some protesters had official bench trials, took the stand and were cross-examined by prosecutors like City Attorney James Ferguson.

And others still had jury trials. Campbell, Adams, Chase, Dunlap and Pinchback were tried by a jury after they conducted a sit-in at a Danville Howard Johnson’s restaurant and were charged with trespassing.

The all-white jury found the five defendants guilty, sentencing each of them to a $100 fine. A transcript of this trial is available on microfilm at the Library of Virginia.

Moore-Batson said she didn’t ever go to the courthouse outside of her own required appearances, even though she had friends who also had to go to court.

“You have to remember, at that time, I’m not sure if there was a designated section for Black people to sit, because everything was still segregated,” she said. “At the courthouse, we couldn’t even use the regular elevators. The only elevator that we could use was the freight elevator with the trash cans and all kinds of stuff.”

Moore-Batson said she can’t remember whether she went to court before or after going to jail, where she spent about a week with other protesters for violating the injunction.

But she does remember being back in court several years later, in the late 1960s. By this point, she had left Danville and was living in New York City, she said.

“I had received a telegram that I needed to be in Danville to appear,” Moore-Batson said.

Several other protesters had to appear in court with Moore-Batson, she said. A team of defense attorneys was trying to get the 1963 charges removed from their records.

“I can’t remember if that was ever done,” she said. “If I remember correctly, they just called out names and we had to take a seat. We never testified or anything like that. Everything was done by the team of attorneys who represented us. I never heard anything more from the federal system or local Danville court after that.”

Moore-Batson remembers Ruth Harvey Charity, one of her attorneys, who eventually became the first Black woman on Danville’s city council in 1970.

Charity worked with other local and national lawyers on these cases, including Jerry Williams Sr., a local Black attorney. His son, Jerry Williams Jr., is still a practicing attorney in Danville.

The younger Williams was a high schooler during the 1963 protests, like most of the other demonstrators. But he was attending a private high school out of town and wasn’t in Danville during the movement.

The night of Bloody Monday, he came back to Danville on a bus because his school year had ended. But his parents didn’t want him to participate in the protests.

“I was anxious to get involved, but my parents said, at this juncture, you need to not be involved in this, because you need to go back to school in the fall,” he said.

Later in life, his father did share some stories about defending protesters, but they didn’t talk about it often, Williams said.

“Occasionally my father would discuss things [about the trials] with my brother and I, but not in detail,” he said. “I came back [to Danville] in 1973, and there were still some cases lingering … but it wasn’t as contentious as it had been 10 years before.”

Williams, Wilson and Moore-Batson all said that many of the protesters have since died or moved out of town.

“There’s so few of us now,” Moore-Batson said. “People have left and are still leaving.”

That’s one reason it’s important to preserve the court records, said Gaidmore, who now works at the library at the College of William & Mary. He was one of the first archivists assigned to this collection during his time with the Library of Virginia.

“For the families of the protesters, their children, for them to look at individual case files and say, ‘Wow, my father and mother did all they could. They didn’t just sit on the sidelines. They fought for my rights and they participated in this and they experienced violence,’” Gaidmore said.

* * *

“This court has thrown open to us the opportunity to beg pardon. … I don’t recall reading historically that anybody begged pardon for throwing the tea in Boston Harbor that belonged to and was private property of the East India Company. I don’t remember anybody begging pardon to King George for violating any rule or regulation that he made. … I have heard no one say that we’re sorry for Negroes being kept in slavery for 350 years, we’re sorry for the 100 years of. … segregation, denial of equal opportunity, discrimination. Yet, because we struggled legitimately in terms of the American tradition for the things that we believe are rightfully ours, we must be expected to beg pardon.”

— The Rev. L.W. Chase’s 1966 statement to the court about his participation in the demonstrations. The jury found him guilty of violating the injunction.

In 1999, Gibson contacted the Library of Virginia to ask them to help preserve this collection. Today, visitors at either the Danville courthouse or the Library of Virginia can look at microfilm transcripts of the court documents and listen to the audio on CD.

The collection spans the 10 years from 1963 to 1973. It includes individual case files for the 254 people arrested and over 85 hours of testimony. While the paper documents cover the entire decade of trials, the audio material only includes trials from 1966 and 1967.

Some of these audio files are mundane — readings of court dockets and roll calls. But some include testimony from protesters, like Paul Price, who describes in one recording how a police officer hit him over the head with a nightstick, and from others involved, like police officers.

The audio files were originally recorded onto Dictabelts by a Dictaphone machine, a recording device that was popular in courtrooms and offices in the 1960s.

A Dictaphone even ran in the judge’s chambers and captured arguments between Aiken and the attorneys about a variety of matters, like whether to consolidate cases.

This audio was the “greatest surprise” of the collection, Gibson said. Hearing the voices of the protesters, attorneys, police officers and Aiken is much more powerful than reading written transcripts, he said.

“To me, that was one of the most valuable assets within the whole group of information,” Gibson said.

This audio was converted from its Dictabelt format onto CDs with the help of a grant from the Library of Virginia’s Circuit Court Records Preservation Program.

The grants are funded by a portion of the fees collected by circuit court clerks and awarded to clerks to aid in the preservation of their court records, said Library of Virginia archivist Greg Crawford.

“We were able to work with the [Danville] clerk’s office to give them a grant to … transfer the audio from those antiquated Dictabelts and turn them into digital audio made available on CD,” Crawford said.

And now, another project is underway at the library to move both the audio and microfilm images to digitized files online, he said.

So far, the Library of Virginia hasn’t gotten many visitors who are interested in this collection, Crawford said. This may be because people don’t know about it, or because they are unable to come to the library in person, he said.

“We hope that by making this available online, that will increase the accessibility, because right now, you have to come to the Library of Virginia to look at the microfilm and listen to the audio on CD,” Crawford said.

There’s no concrete timeline for the digitization projects. But Crawford said he’s excited to be able to share these records with a wider audience and make them available to future generations because they are an important part of history.

“Giving everyone’s perspective, not just the county sheriff’s perspective or the white perspective, but all diverse and inclusive perspectives, that’s what the Circuit Court Records Preservation Program is all about.” Crawford said. “There are people’s voices on these records that have been cooped up in a drawer in a courthouse for years, and we’re trying to let those voices be heard.”

This story is part of Cardinal News’ larger Bloody Monday reporting. Read the full collection of stories.